On computer keyboards

- First draft

- 2024-09-08

- Latest draft

- 2025-10-21

When C. Latham Sholes in the 1870's was figuring out the optimal arrangement for the keys of his new invention, little did he know about the suffering it would cause to computer users a century and a half later.

For millennia we used some sort of stick to scribble words on some surface, from clay tablets to pen and paper. Now that mode of creating text is more and more a thing of the past, computer keyboard having become the mainstream method for pushing letters. But why are the keys arranged in such peculiar way?

Before typewriter there was handwriting

Until the final decades of the 19th century, the only way to write something was to write it by hand, put that pen on paper. Some did it faster, some neater, but in general writing was a slow and messy process. There was the printing press that allowed the most valuable of texts to be printed, resulting in a clean and easily readable output. But even after the invention of the rotary press, which dramatically increased the throughput, printing was relatively slow, expensive, and very much out of reach for regular everyday writing tasks.

There had been attempts to create a writing machine, but none really caught on before C. Latham Sholes' version, which was both simpler and more efficient than its predecessors. The typewriting machine had type headed hammers or typebars: levers having the letter type embossed on the other end, pressing the keys would swing the lever, the type head then hitting the paper through inked ribbon, and gravity taking care of returning the lever to its resting position.

Jamming hammers

One of the many problems the early design iterations had to solve was the typebars getting jammed. E.g. letters "S" and "T" are next to each other in alphabetical order, but "T" also following "S" often in English text. As the typebars were initially in alphabetical order, this kind of letter pairs resulted in frequent jamming. Through analysis of letter frequencies and a lot of trial-and-error such an order was found, that the typebars most of the time would not get stuck. The leftmost keys of the top letter row gave the name for this key layout: QWERTY.

Another consequence of the lever based design was the staggering of the keys: each row was offset from the previous row to give space to the lever mechanism. For human hand anatomy straight columns would provide a more natural finger movement, but this design did not allow for such layout.

In the following decades these mechanical limitations became irrelevant with electric typewriters and the letter types moving from bars to rotating discs and balls. There was also increasing awareness of the inefficiencies of the QWERTY layout: awkward finger stretching was required for common letter combinations and many of the most used letters were away from the central hand position, the home row. Especially August Dvorak's passionate work in the 1930's with the eponymous layout is worth mentioning. Nevertheless, the keyboard layout had become so familiar to the typing masses, that any change was doomed to be a commercial failure.

So even today the device you are reading this on most probably has a QWERTY keyboard, even on mobile phones, where the last ties to the physical world have been severed, the keyboard being just a picture drawn on a glass surface that you tap with your fingers. This is a prime example of path dependency: things are designed this way, because they were designed before like this, regardless of the original design constraints having disappeared many, many design generations ago.

Enter computer

Around the same time as poor Dvorak was shedding tears over typists' pain, an English mathematician Alan Turing came up with an abstract machine that could implement any algorithm - a procession of steps to solve a mathematical problem. Turing intended the machine solely as an abstract model, a mental tool to help prove the uncomputability of the Entscheidungsproblem. But already a decade later his machine had been made concrete. These first computers were programmed by changing the wiring of the computer with plug boards, or flicking switches. Later came punched paper tapes and cards.

Later, as computers got so much more efficient, that flicking the switches or feeding the punched cards took more time than actually computing the results, the idea of time-sharing was conceived. On a time-sharing system multiple end-points or terminals were connected to a single computer, so that multiple users could be using it simultaneously. With this approach a new need emerged: how to handle input and output with these remote end-points.

Telegraphy was originally purely mechanical and visual means of remote communication via a series of relay towers. During the 19th century communication was revolutionized by electric telegraphy, operators tapping the telegraph key to produce a series of dits and dahs. Interestingly, it was a telegraph key that Sholes repurposed for his first typewriter prototype. By the time the computers appeared most telegraphy was handed with devices looking a lot like electric typewriters: hitting the keys sent signals down the wire, and received signals caused letters to be typed on the paper roll. These devices - teletypewriters - were the perfect match for the needs of computer terminals. So from the 1960's onward a keyboard became the most common way to operate a computer.

Shifting layers

The very first typewriters had only uppercase letters: even with the 26 letters of the English alphabet, with numbers and some punctuation, there were quite a bit of keys. Doubling the letter count for lowercase would have made the keyboard unwieldy. Later models added a second character on each of the typebars, so that raising the paper cylinder with a shifting key would make the second character to be typed. There were also competing designs with three characters for each typebar and two distinct shift keys. The simpler, easier but less advanced, however won the shift wars, and that's the way typewriters work even today.

Computers (and teletypewriters too for that matter) required more though, and having a separate key for each additional function would again made the keyboards reach ludicrous proportions. A new kind of shift key was introduced so that the control commands could be sent using the same alphanumeric keys as text was typed with. This key became eventually know as the control key, or just CTRL among friends.

There were now three keyboards layered on one set of physical keys: uppercase, lowercase, and control. But as computers spread yet another novel requirement became apparent: entering letters not found in the English alphabet. Some national keyboard variations added a couple of keys for their Äs and Ös, but that would not suffice for long, so keyboards begot another layer for these alternative characters, summoned with the ALT key. Modern graphical user interfaces (GUI) added still another layer shifting key: the GUI key is more commonly known as Win-key among the Windows users or Command-key on Apple computers (which in their early days had an Apple key).

These keys that change the keyboard layer are commonly called modifier key, and currently the Shift, CTRL, ALT, and GUI is the baseline that all computers have, but often laptops have an extra Fn-key.

Finger contortionist

Giving the computer commands is easy with the keyboard: press S together with CTRL (or CMD on Mac) to save your work. Some commands require a bit more: paste text without its formatting is CTRL + Shift + V. Except some applications need CTRL + ALT + Shift + V for the same task. With some applications - like the Photoshop - these torturing keyboard shortcuts with two or three modifier keys are quite common. What is not common however is any sort of ergonomic consideration in assigning the key combinations.

So on top of the misery of QWERTY where the most common letters require stretching your fingers, we now have shortcuts that add an excruciating twist to those stretches, and staggered rows of keys denying the last chance of natural finger movement. But the pain doesn't stop there. As your arms are hanging on the side of of your body, not protruding from your chest, in order to place your poor hands on the keys, you have to twist the wrists in an angle that blocks the veins and nerves.

If anyone today would try to bring to the market something that is as unhealthy as using a computer with regular keyboard they would be swiftly put behind bars for a long time.

At the same time banging those keys remains the fastest way to enter text to a computer. For slower typists speech could actually be faster, but you wouldn't want to work in that open plan office. Is there a way to make those old keys any less painful?

Key alternatives

The afore mentioned path dependency - or peoples insistence to use the familiar things and reluctance to learn new things - is actually the only thing holding back healthier typing.

The first steps to the right direction were taken already by Dvorak, but that is only one part of the solution. Perhaps the most important improvement is splitting the keyboard into two halves which can be independently positioned so that the wrists can remain straight. The following steps include ditching the staggered rows and having straight columns of keys, then staggering those columns to accommodate for different lengths of fingers in a hand. Each keyboard half can be tilted sideways (tented) to allow the arms even more natural position.

But still there are situations when finger stretching can't be avoided, e.g. the number row is two rows above the home row. The solution to this is having less keys, but more layers. No need for a far lying number row, when a number layer can put the digits directly under your fingers on the home row. But to switch to the number layer we need another modifier key, in addition to those making shortcuts painful. One possible answer to that problem is to move the modifier keys for thumbs - the two strongest fingers which so far have jointly operated a single key, the space bar.

There are a growing number of commercial options, like the Voyager by ZSA, Defy by Dygma, and Glove80 by MoErgo. There are also a large number of less dramatic departures from the tradition, these might serve as a gentler stepping stone to more ergonomic world.

My personal solution

A couple years ago I started pondering on alternatives to the traditional QWERTY keyboard, and ended up with the previous offering by ZSA, the Moonlander. I fell in love with it pretty much instantly, but over time I became aware of its shortcomings. There were still too many keys, I still had to stretch my fingers.

My first solution was to remove some keys and cover the holes:

That was already a much more pleasant typing experience. But there was still some struggle: the pinky felt comfortable on just one key, pressing the key above or below just felt forcing it. Also the overall positioning of the keys was not quite perfect. Eventually I came to the conclusion that to get a perfect keyboard, it would have to be tailor made to my hands. And in practice it meant that I had to learn how to design and build one.

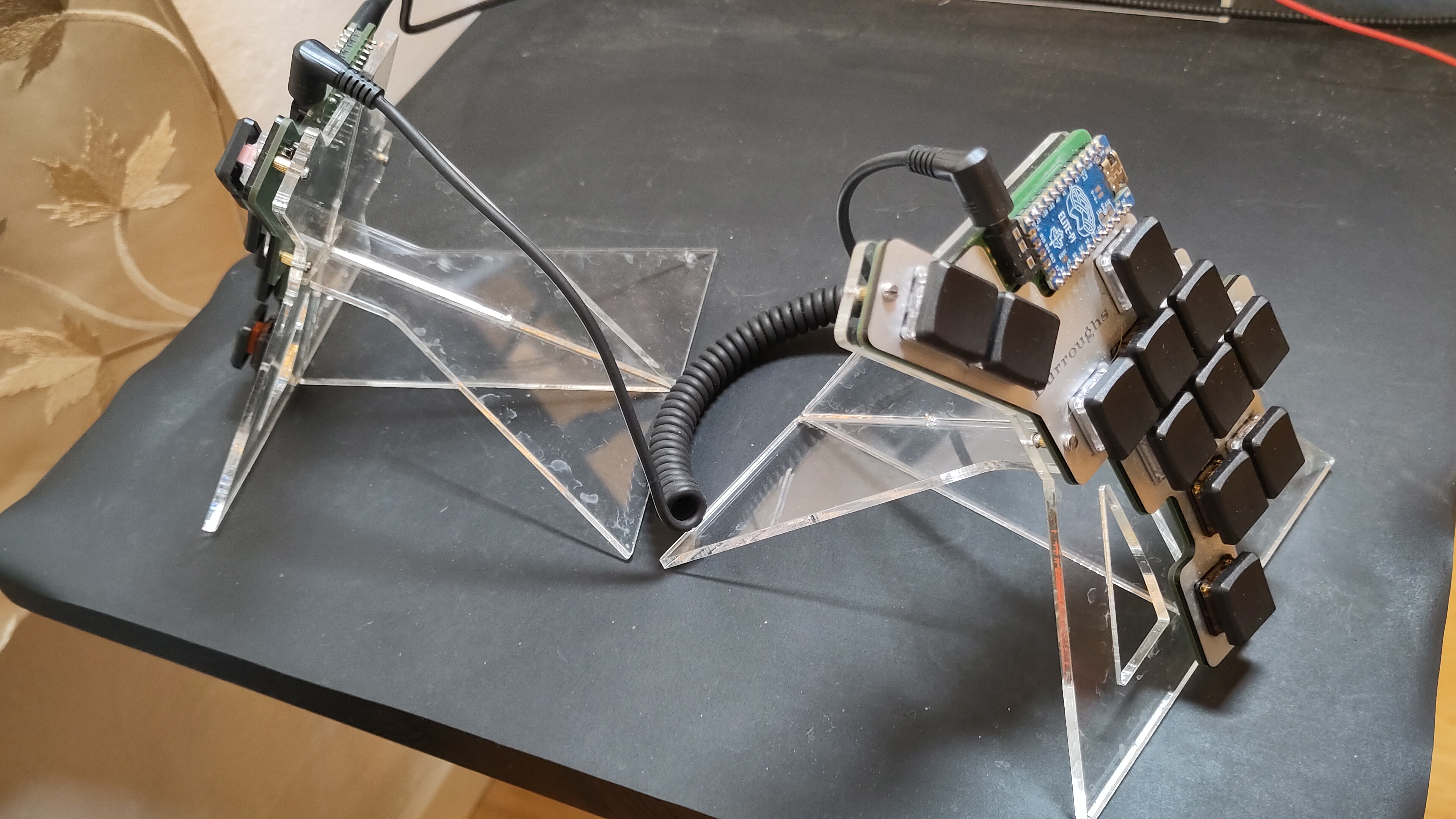

After some paper prototypes (sticking keys on a piece of paper with blue tack) and a plenty of studying this was the result:

As you can see, each halve has only 12 keys, and English alphabet has 26 letters. The trick was to split the letters to two layers, the most common ones on the base layer, and the rest accessed with a modifier key. One of the layers has keys for moving the mouse pointer, so that I don't need to move my hand to reach the mouse. The tenting angle is 60 degrees, which I find optimal for my arms. Since the above picture was taken the stand has evolved a bit, as the original attempt was not quite stable enough. But now I feel that there really couldn't be a better keyboard for my hands.

But a better solution has nevertheless been brewing. While a keyboard couldn't get any better, the "board" is something that could be removed: as the board must be on a desk (or hanging from my belt - also rather comfortable approach) my arms have to be more or less stationary. The optimal solution would have keys where ever my hands are, not attached to any board. So the keys must be somehow attached to the hand, with one key for each finger. I have started the prototyping, but nothing ready yet. More on this then on some future iteration of this draft.